The script of my YouTube video for those who prefer the written medium.

Introduction

While the medium of visual novels sees more variety and diversity day after day, at the center of it all sits experiences centered on good old-fashioned love. These romance-centered games may be classified by various different labels, each with their own distinct nuances:

just to name a few.

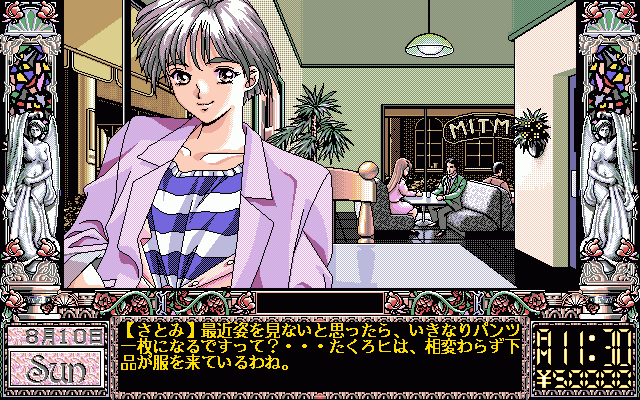

Whichever one of these often times overlapping categories they fall into, however, their impact on carving the medium of visual novels a niche within the greater otaku sphere is undeniable. I mean, when the average person in the West thinks of the term “visual novel”, assuming they even know at least roughly what it refers to, the first thing that comes to mind is probably something like this.

Or this.

Or this.

as countless parodies won’t hesitate for even a second to point out.

But how did we get to this point? How did we go from clunkily warping between point-and-click pixel-art vistas, adventure-game style, to paging through translucent textboxes overlapping expressive anime-style character portraits, against a canvas of gorgeously rendered CG stills? How did we go from a landscape full of ostensibly racy and puerile erotica to the heartwarming embrace of deeply moving and passionate tales of budding adolescent romance?

While it certainly won’t be an exhaustive or rigorously in-depth account, this video charts the general course of that long and fascinating journey.

Crash Course on the History of Eroge: The 1980s and Early 1990s

The origins of the modern day romance visual novel are steeped in titillation, tracing back to the early 1980s, a period of time defined by a craze of inventive technological dabbling, of pushing the boundaries of what could be achieved on the rapidly advancing computer hardware of the era. In particular, a studio named Koei, creators of the Dynasty Warriors franchise, released a simulated pornographic marital aid for couples, titled Night Life in 1982 for the PC-88, which is often hailed as the first eroge, the term itself being short for “erotic game” and referring to games containing explicit adult content, most often as the core focus.

Night Life itself, however, barely qualified as a game, in retrospect, bringing us to one of the first eroge with at least a modicum of meaningful player input: Lolita Syndrome in 1983 by Enix, which incidentally is also the earliest game documented in VNDB. With the pedigree of a publishing studio like Enix, it’s hard to believe, even looking at the risque cover art, that Lolita Syndrome was pretty much straight up B-movie-esque sexploitation: with the scenario based around rooms behind most of which lie torture minigames where the goal is to save five women from impending demise. Success results in disrobement of the full frontal nudity variety, while failure nets you a screen full of gore and giblets.

Though the game left somewhat of a black mark on Enix’s legacy in some circles, to the studio’s credit, it only officially served as the distributor, as the title was developed as part of Enix’s Game Hobby Program Contest, which also yielded works such as Love Match Tennis, kickstarting the career of Dragon Quest creator Yuji Horii.

To break out of the cycle of gratuitous exhibitionism, a bit of heart was desperately needed. Enter Girl’s Garden, released by Sega in 1984 for the SG-1000, a game which certainly helped bridge the gap, if only via super-simplified simulacrum.

In Girl’s Garden, you take on the role of a young girl whose goal it is to win the heart of a boy by gathering a specific number of flowers and presenting them to him before the in-game time limit expires, indicating that another girl has caught his fancy. While there’s no dialogue or really anything of substance regarding this highly abstracted interpersonal intimacy, Girl’s Garden‘s jaunty and wholesome atmosphere made for a wonderfully effective detox coming off the heels of the likes of Lolita Syndrome and its brethren. Incidentally, Girl’s Garden was the debut work of Sonic the Hedgehog and Phantasy Star creator Yuji Naka as well as Sega music composer Hiroshi Kawaguchi.

Moving on now to the familiar embrace of the graphical adventure game which itself saw a massive surge in popularity starting in the mid 80s, we arrive at Tenshitachi no gogo, released in 1985 by JAST, a PC game which all-but inextricably tied romance games of the era to the instantly-recognizable aesthetic of colorful, anime/manga-esque character portraits adorning dialogue-heavy scrolling text windows, albeit with the imagery rendered in a largely nascent and primitive manner, given the limitations of mid 80s computer hardware.

Tenshitachi no gogo carried forth the idea from Girl’s Garden of having to “work” for the end goal of winning the affection of the lead heroine: Yumiko Shiraishi, the star of the high school’s tennis club, by interacting and forming relationships with the people around her, already adding layers of complexity to the crude smut-fests of just two or three years prior.

As far as applying the trappings of romance to different genres, three games towards the end of this time period come to mind: Rance -Quest for Hikari-, Dragon Knight, and Toushin Toshi. Released in 1989 by Alicesoft, Quest for Hikari was the first game in the Rance series, a set of fantasy adventure games which has endured to this day thanks to its notoriety within the hentai scene. The game was notable for infusing the traditional graphical adventure framework with RPG stat-building and combat mechanics resulting one of the first eroge to feature something more than a primitive player input engine.

Just months later at the end of 1989, Studio ELF would release Dragon Knight, also a high fantasy eroge, but one more in the style of a classic dungeon crawler. Alicesoft would then supplement its roster with Toushin Toshi in 1990 and sequels to all three titles were released throughout the following decade, sparking something of a competition between the two studios, known colloquially as ELF of the East, Alice of the West: ELF being situated in Tokyo, and Alicesoft being situated in Osaka.

Finally, closing out this period is Cobra Mission: a point-and-click adventure game style game released in 1991. Cobra was notable for being the first eroge to be licensed and localized for the West, and while it was critically panned, it nonetheless set the stage for the slow proliferation of this niche among Western audiences.

The 1990s: The Birth of Dating Sims

The early 90s marked a major milestone for this blossoming phenomena, starting off with a bit of turbulence with the release of Saori: Bishoujo-tachi no Yakata, from publisher Kirara, an offshoot of JAST. When a copy of the game was stolen by a junior high school student, the police’s investigation led them to uncover the extent of the graphic and disturbing adult content in the game, which led to the arrest of the leadership of the production company on charges of possession of obscene material with intent to resell. This was known as “Saori jiken” or “The Saori Incident” and ultimately, the game was pulled from shelves and re-released with all adult content censored. The Saori incident also led to the establishment of the Ethics Organization of Computer Software, known colloquially as “Sofurin”, whose role it was to provide industry-wide regulatory guidelines for games containing mature content.

The Saori Incident was followed by a period of growth and acceptance for romance titles as they would finally gain an established foothold within the wider video game bubble, starting with the first game that is widely regarded to have set the standard for the modern day dating sim: Dōkyūsei released by ELF in 1992.

Building upon the character exploration framework introduced by Tenshitachi no gogo and its sequels, Dokyusei pioneered the unorthodox storytelling mechanic of changing aspects of the narrative and the course of the story in accordance with different options taken during interactions with each of the various girls that make up the game’s cast, essentially allowing the protagonist to win over the affection of a specific heroine, completely upending the at-the-time-universally-accepted purely linear storytelling model. This approach was based on the idea of granting the player a sense of agency and personal control over the narrative: generating radically different experiences uniquely personalized to one’s quote-unquote “type” of girl. This, in turn, set the foundation for a narrative crafted around multiple, independent story arcs or “routes” as they are referred to in modern visual novel terminology, a hallmark of how romance VNs are structured in modern times, occasionally referred to using the term “harem”, such as in the phrase “harem game” or “harem genre”.

While Dokyusei debuted to admirable fanfare, Tokimeki Memorial is what really enabled this niche subculture to hit its stride. Released by 1994 for the PC-Engine by the towering entertainment juggernaut Konami, Tokimeki Memorial all but established the dating game subgenre and in doing so, achieved a level of mainstream success that cemented this brand of romance games within the public consciousness. Tokimeki Memorial was quasi-inspired by Square’s Miho Nakayama’s Tokimeki High School released in 1987, a game which was incidentally designed by Final Fantasy creator, Hironobu Sakaguchi. In retrospect, however, High School was little more than a crude prototype and it was Memorial that saw that creative vision through to completion and then some.

In contrast to Tenshitachi no gogo and Dokyusei’s barebones decision-making based gameplay system, Tokimeki Memorial is an overclocked monolith of a mainframe: a well-oiled high school social simulation engine, sporting an elaborate stat-building system for the protagonist alongside an equally elaborate relationship-tracking system for each and every one of the myriad heroines, all flowing to the temporal beat of a meticulous three-year day-by-day calendar, resulting a sprawling, borderline-intractable labyrinth of a narrative flowchart.

Of note is that Tokimeki Memorial doesn’t feature any actual explicit content, fully distancing itself from the eroge label, something that definitely enabled it to garner mainstream appeal. Its overwhelming success and popularity spawned numerous ports on different home consoles, unheard of for a romance game as well as numerous spinoffs, one of which was Tokimeki Memorial Girl’s Side in 2002, a high school dating sim geared towards female audiences. This line of female-oriented romance games known as otome games or “maiden games”, was first established by Koei for the Super Famicom in 1994 with Angelique, a sci-fi medieval fantasy that was helmed by an all-women team and aimed at slightly younger audiences in their teens, thus containing no adult content, as well as being steeped in tropes and conventions from popular shojo manga of the era.

The Rise of Visual Novels

Similar to how Tokimeki Memorial took the graphic adventure game framework and crafted a full-fledged virtual life simulator around it, a studio named Chunsoft led the framework down a parallel path, veering away from complexity and even closer towards minimalism. Enter the horror mystery Otogirsou in 1992, which more or less removed player interaction entirely, resulting in what was ostensibly a novel in digital form, or “sound novel” as the title was officially marketed as.

Otogirisou’s success paved the way for a studio known as Leaf to release their own take on the emerging paradigm: Shizuku in 1996, the first game marketed as a visual novel. Like Otogirisou, Shizuku started with a foundation of horror-mystery but then proceeded to layer in elements of eroge, at last giving birth to the first romance game in visual novel form.

While Shizuku served as the progenitor, it wasn’t until Leaf released To Heart in 1997 when commotion began to brew. Unlike Shizuku which was, as mentioned, in the vein of Otogirisou and its ilk, To Heart staunchly adhered to traditional high school slice-of-life sensibilities, with an ensemble deliberately molded from all the standard female character archetypes, very similar to Tokimeki Memorial, enabling it to do for romance VNs what Memorial did for dating sims: land the emergent subgenre squarely in front of the eyes of more mainstream audiences. Unlike Tokimeki Memorial, however, To Heart did contain erotic content, making its accomplishments all the more laudable: in fact, it was the first eroge to have its theme songs feature in karaoke systems across Japan.

The game’s PlayStation port in 1999 did feature an all-ages version, however, likely driven by its widespread success, a trend which would become increasingly common as more and more eroge made their way towards the top of the sales charts.

Storytelling-wise, To Heart was also notable for having the overarching narrative be in lockstep with each individual heroine’s character arc, instead of the two developed independent of each other. According to scenario writer Tatsuya Takahashi, who had also helmed Leaf’s previous releases, Shizuku and Kizuato, and who would go on to handle script composition and screenplay for popular anime titles such as Eromanga-sensei and Idolmaster, the narrative for To Heart hadn’t even entered the planning stage until after the character designs had been completed: a rarity in those days, but has more or less become the norm in today’s merchandise-driven landscape. Along the same lines, To Heart was explicitly designed from the outset as a mixed media release, with the expectation of eventually being ported to home consoles and adapted across various mediums.

The 2000s: Narrative-focused Romance

Of course, a success story like To Heart isn’t truly a success story unless it triggers an opening of floodgates, an avalanche of hopefuls following suit, eager to replicate the now demonstrably winning model. A studio named Tactics would release several romance VNs in quick succession around the time To Heart was knee deep in accolades, with One: Kagayaku Kisetsu e in 1998 as a particularly noteworthy entry as the game featured Itaru Hinoue as art director and character designer, Shinji Orito and OdiakeS as musical composers, and Naoki Hisaya and Jun Maeda as scenario writers.

If you recognize any of those names, then you already know what’s coming down the pike: these members formed the core production team for One and due to creative differences after the game’s release, the team decided to start their own studio under Visualarts, by the name of Key.

The formation of Key ushered in a new era of romance games: more plot-heavy stories evoking feelings of melancholy and wistfulness. Stories which would start out perfectly innocent and joyful, but, through inevitable heartbreaking tragedy, culminate in an outburst of raw, tear-stained catharsis. Stories that would conclude by imploring us to pause and reflect on the meaning of human relationships and how we may take to heart what these characters have endured to perhaps better our own lives. Stories that seemed to all but eschew wanton lasciviousness in favor of romantic quote-unquote “purity”.

“At first I was surprised that bishōjo games had come to a

point where they could have such an impact on players, but then I came to think of the

tears as a sign of our ultimate success.”

Jun Maeda

These games exploded in popularity to the point where they carved out a new category for themselves: “Nakige” or crying game, though some may refer to them as “Utsuge”, which means “depression game”. Key’s debut release was Kanon in 1999, one of the most influential and historically important visual novels not just with regard to eroge or romance games, but in general, selling over 300,000 copies. Upon achieving such a high level of success primarily on the strength of the narrative of both Kanon and its subsequent release, Air, in 2001, Key slowly began distancing itself from the eroge label, releasing all-ages versions of both Kanon and Air, and eventually dispensing with the adult content entirely with the release of Clannad in 2004.

While Key works, very much led the charge in the early ‘00s, there were a bevy of other prominent titles that also helped mold this zeitgeist such as Kana Imouto or Symphonic Rain.

While this shift was undeniably the most impactful and enduring trend, there were definitely other attempts at innovation, attempts at transplanting the romance game paradigm among new and interesting scenery. Sakura Wars by Sega in 1996 for instance saw a melding of turn based strategy and dating sim elements. The Persona line of games by Atlus, for example, would eventually incorporate a calendar-based dating sim framework alongside its core of contemporary urban-fantasy turn-based RPG.

And of course, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention YU-NO by ELF, also released in 1996 which would become renowned for introducing groundbreaking science-fiction based narrative and gameplay elements, going on to inspire many creative talents and properties in the visual novel scene, including, but not limited to, behemoths such as the SCI-ADV line of games, Steins;Gate , in particular, and Type Moon’s Fate/stay night.

2000s – present: Diversification

From here romance games only continued barreling down the path of diversification, with some titles remaining faithful to this now standard convention, ensuring the torch is carried forward for generations to come…

some taking a slight or more-than-slight subversive bent, often achieving at least some measurable level of mainstream notoriety because of it…

and a good chunk partially or fully leveraging the multi-route, choose-your-own-heroine-to-romance framework and embedding it as a narrative tenet of a game that may or may not have anything to do with romance at its core, from mysteries, to thrillers, to sci-fi action, the list goes on and on and on.

And while the heyday of romance games may have crested in Japan during the early 00s, in the West, there has certainly been no shortage of grassroots, indie titles sallying forth with unique and imaginative sensibilities of their own, with two notable standouts being Katawa Shoujo in 2012, and the subversive and deconstructive Doki Doki Literature Club in 2017, though the list grows longer and more innovative with each passing day.

References

Bishoujo Game, Wikipeda, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bish%C5%8Djo_game

Eroge, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eroge

A History of Eroge, Satoshi Todome, https://archive.ph/20121205102947/http://www.shii.org/geekstories/eroge.html#selection-9.0-9.18

Dating Simulation Games: Romance, Sex, and Love in Virtual Japan, Emily Taylor, https://www.amazon.com/dp/B01FQ6IL3A/ref=dp-kindle-redirect?_encoding=UTF8&btkr=1

Introducing the history and masterpieces of eroge with CG, https://minimal05.com/erogame/

Introduce the history of eroge, https://www.ima-ero.com/lecture/history1/

History and Genesis of Adult Games, http://3log.moe/blog-entry-17.html

TINAMIX INTERVIEW SPECIAL Leaf Takaya Takahashi&Harada Woodal, http://www.tinami.com/x/interview/04/index.html

Bishōjo Games: ‘Techno-Intimacy’ and the Virtually Human in Japan, Patrick W. Galbraith, http://gamestudies.org/1102/articles/galbraith

The Politics of Imagination: Virtual Regulation and the Ethics of Affect in Japan, Patrick W. Galbraith, https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/10161/14371/Galbraith_duke_0066D_13809.pdf?

The Impact of Telepresence on Cultural Transmission through Bishoujo Games, Matthew T. Jones, https://web.archive.org/web/20120620120235/http://www.psychnology.org/File/PNJ3%283%29/PSYCHNOLOGY_JOURNAL_3_3_JONES.pdf

ACTION BUTTON REVIEWS Tokimeki Memorial, Tim Rogers, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xb-DtICmPTY